The limits of complexity and the Maillard phase.

Last updated: 19 Jan 2026

489 Views

The Limits of Complexity and the Maillard Phase

Many roasters try to extend the Maillard Phase in hopes of increasing complexity or achieving more layered flavors. But why do the results sometimes turn out to be the exact opposite?

This article may offer an answer.

⸻

What Is the Maillard Phase (MAI Phase)?

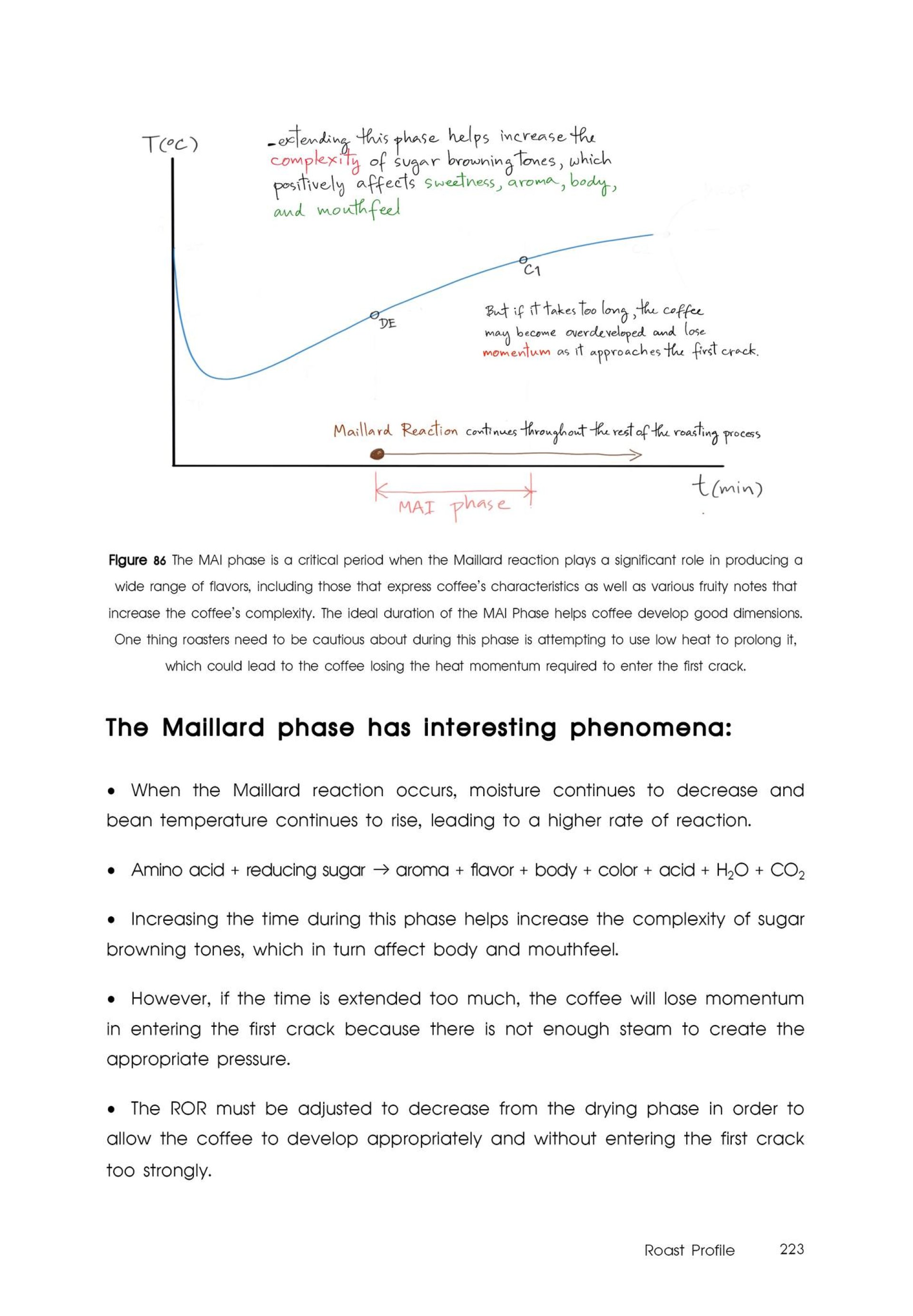

A roast profile is typically divided into three main stages: the initial Drying Phase, the middle Maillard Phase, and the final Development Time.

The Maillard Phase (MAI Phase) refers to the period from Dry End (DE)—when the coffee beans begin to undergo Maillard reactions in a noticeable way—until the onset of First Crack (the first audible, continuous cracking sounds). Practically speaking, Dry End is often identified when the beans begin turning brown and emit aromas reminiscent of toasted bread.

The commonly referenced temperature range for this phase is approximately 160–190°C, although the exact numbers may vary depending on roaster design, probe placement, and sensor type.

The Maillard reaction is a browning reaction that occurs during roasting, creating a wide range of aroma and flavor compounds that evolve with time and temperature. It relies on two main precursor groups: reducing sugars and amino acids. As bean temperature increases, this reaction becomes more intense and continues throughout the roast until roasting is stopped. This means that even after First Crack, Maillard reactions are still ongoing.

Calling the period from Dry End to First Crack the “Maillard Phase” mainly indicates that Maillard reactions dominate during this window, before other chemical reactions begin to strongly compete. Toward the end of this phase, there may be some overlap, as pyrolysis and caramelization can begin slightly before First Crack.

⸻

Beliefs About Fruity–Floral Notes, Complexity, and MAI Duration

Many roasters believe that if they want pronounced fruity and floral characteristics—multiple notes layered together—they should extend the Maillard Phase. The assumption is that a longer reaction time will generate more of these aromatic compounds, along with increased sweetness. Roasters who follow this approach often reduce heat input, or “ease off the fire,” to lengthen this phase.

The problem is that this approach does not work equally well for everyone. Some roasters do see improvement when they extend the MAI Phase, but others experience the opposite: muted aromas, green or raw nut–like flavors, or floral and fruity notes that never fully develop. In more severe cases, acidity and sweetness may actually decrease.

Many roasters have likely experienced this firsthand: extending the MAI Phase initially improves the cup, but pushing it even further makes the result worse.

This suggests that there is a limit to how long the Maillard Phase can beneficially contribute to overall flavor, and that longer is not always better—though too short is also problematic.

Why does this happen?

I would like to propose an explanation based on the concept of Good Reaction.

⸻

Good Reaction and Well-Balanced Heat Momentum

If we consider coffee flavor as the result of various reactions occurring during roasting, then temperature determines what kinds of compounds are formed, while the reaction rate determines how quickly and how much of those compounds are produced.

A suitable reaction rate at a given moment allows desirable flavor compounds to develop fully—especially during the critical window around First Crack, from slightly before First Crack to some time after, until the beans transition from a partially cooked state to being fully cooked throughout.

I call the desirable set of reactions occurring around First Crack a Good Reaction.

How do we know what constitutes a good reaction? Can it be quantified? I believe it can be translated into measurable values, but before going there, let’s clarify what “good” means by imagining its opposite—not good reactions.

1. Too much heat

When roasting with excessive heat, everything happens too quickly. First Crack arrives early, bean temperature rises rapidly, and the coffee often tastes burnt or bitter on the surface while the interior remains sharp and sour. The flavor balance is poor—sometimes even the roaster is unsure whether to call the result a light or medium roast. Most disappointing is the lack of sweetness and aftertaste. With excessive heat, the window for developing clean sweetness and pleasant aromas is very short before the roast jumps straight into harsh, carbonized, bitter reactions.

2. Too little heat

When heat is too low, color development is slow, bean expansion is limited, and First Crack arrives late at a relatively high temperature. The resulting coffee often tastes flat, with little clarity in acidity. To remove green flavors, the roaster must extend development time, but once the coffee is finally cooked, roasty flavors often dominate as an unintended byproduct.

These two examples illustrate not good reactions, helping us better visualize what a good reaction should look like.

If we observe carefully, we can see that good reactions are closely tied to heat input during roasting. More precisely, they are linked to heat momentum—the thermal momentum transferred from the roasting system into the coffee beans.

In summary, good reactions support balanced flavor development, enhancing acidity, sweetness, and aroma. If we can control heat so that good reactions occur—especially from First Crack into Development Time—the coffee will reach full flavor expression, including complexity.

⸻

Entering First Crack With Good Reaction

The key lies in entering First Crack with good reaction, which requires well-balanced heat momentum—neither too strong nor too weak. This thermal momentum can be observed through the Rate of Rise (ROR) of bean temperature.

⸻

MAI Duration as a Tool for Balancing Heat Momentum

In reality, the duration of the Maillard Phase reflects how the roaster manages heat. It determines how the beans approach First Crack with an appropriate ROR—supporting good reaction and good development.

• Long MAI Phase → lower heat input → weaker heat momentum

• Short MAI Phase → higher heat input → stronger heat momentum

This explains why extending the MAI Phase can improve results up to a point, but leads to poorer outcomes once it exceeds the optimal range.

At this point, we should redefine the Maillard Phase:

It is the phase that prepares and delivers heat momentum into Development Time.

⸻

Practical Guidelines

So, what ROR at First Crack tends to produce good reactions?

Based on my experience and experiments, a suitable ROR at First Crack generally falls between 7–13°C per minute.

A safe-zone MAI duration is around 3 minutes, give or take slightly.

When roasts consistently hit this window, roasting becomes easier and results are more reliable.

Thank you very much for reading to the end.

⸻

Simplicity in Coffee Roasting – English Edition (Thailand Print)

The English edition of Simplicity in Coffee Roasting, printed in Thailand, has now been completed and is officially available. I’m truly happy to see readers following from many countries. If you’re interested in ordering a copy, please contact the admin of the Preda Coffee Roasting House page.

Early Bird Promotion: 15% off—from 2,500 THB to 2,125 THB, valid until the end of January 2026.

Many roasters try to extend the Maillard Phase in hopes of increasing complexity or achieving more layered flavors. But why do the results sometimes turn out to be the exact opposite?

This article may offer an answer.

⸻

What Is the Maillard Phase (MAI Phase)?

A roast profile is typically divided into three main stages: the initial Drying Phase, the middle Maillard Phase, and the final Development Time.

The Maillard Phase (MAI Phase) refers to the period from Dry End (DE)—when the coffee beans begin to undergo Maillard reactions in a noticeable way—until the onset of First Crack (the first audible, continuous cracking sounds). Practically speaking, Dry End is often identified when the beans begin turning brown and emit aromas reminiscent of toasted bread.

The commonly referenced temperature range for this phase is approximately 160–190°C, although the exact numbers may vary depending on roaster design, probe placement, and sensor type.

The Maillard reaction is a browning reaction that occurs during roasting, creating a wide range of aroma and flavor compounds that evolve with time and temperature. It relies on two main precursor groups: reducing sugars and amino acids. As bean temperature increases, this reaction becomes more intense and continues throughout the roast until roasting is stopped. This means that even after First Crack, Maillard reactions are still ongoing.

Calling the period from Dry End to First Crack the “Maillard Phase” mainly indicates that Maillard reactions dominate during this window, before other chemical reactions begin to strongly compete. Toward the end of this phase, there may be some overlap, as pyrolysis and caramelization can begin slightly before First Crack.

⸻

Beliefs About Fruity–Floral Notes, Complexity, and MAI Duration

Many roasters believe that if they want pronounced fruity and floral characteristics—multiple notes layered together—they should extend the Maillard Phase. The assumption is that a longer reaction time will generate more of these aromatic compounds, along with increased sweetness. Roasters who follow this approach often reduce heat input, or “ease off the fire,” to lengthen this phase.

The problem is that this approach does not work equally well for everyone. Some roasters do see improvement when they extend the MAI Phase, but others experience the opposite: muted aromas, green or raw nut–like flavors, or floral and fruity notes that never fully develop. In more severe cases, acidity and sweetness may actually decrease.

Many roasters have likely experienced this firsthand: extending the MAI Phase initially improves the cup, but pushing it even further makes the result worse.

This suggests that there is a limit to how long the Maillard Phase can beneficially contribute to overall flavor, and that longer is not always better—though too short is also problematic.

Why does this happen?

I would like to propose an explanation based on the concept of Good Reaction.

⸻

Good Reaction and Well-Balanced Heat Momentum

If we consider coffee flavor as the result of various reactions occurring during roasting, then temperature determines what kinds of compounds are formed, while the reaction rate determines how quickly and how much of those compounds are produced.

A suitable reaction rate at a given moment allows desirable flavor compounds to develop fully—especially during the critical window around First Crack, from slightly before First Crack to some time after, until the beans transition from a partially cooked state to being fully cooked throughout.

I call the desirable set of reactions occurring around First Crack a Good Reaction.

How do we know what constitutes a good reaction? Can it be quantified? I believe it can be translated into measurable values, but before going there, let’s clarify what “good” means by imagining its opposite—not good reactions.

1. Too much heat

When roasting with excessive heat, everything happens too quickly. First Crack arrives early, bean temperature rises rapidly, and the coffee often tastes burnt or bitter on the surface while the interior remains sharp and sour. The flavor balance is poor—sometimes even the roaster is unsure whether to call the result a light or medium roast. Most disappointing is the lack of sweetness and aftertaste. With excessive heat, the window for developing clean sweetness and pleasant aromas is very short before the roast jumps straight into harsh, carbonized, bitter reactions.

2. Too little heat

When heat is too low, color development is slow, bean expansion is limited, and First Crack arrives late at a relatively high temperature. The resulting coffee often tastes flat, with little clarity in acidity. To remove green flavors, the roaster must extend development time, but once the coffee is finally cooked, roasty flavors often dominate as an unintended byproduct.

These two examples illustrate not good reactions, helping us better visualize what a good reaction should look like.

If we observe carefully, we can see that good reactions are closely tied to heat input during roasting. More precisely, they are linked to heat momentum—the thermal momentum transferred from the roasting system into the coffee beans.

In summary, good reactions support balanced flavor development, enhancing acidity, sweetness, and aroma. If we can control heat so that good reactions occur—especially from First Crack into Development Time—the coffee will reach full flavor expression, including complexity.

⸻

Entering First Crack With Good Reaction

The key lies in entering First Crack with good reaction, which requires well-balanced heat momentum—neither too strong nor too weak. This thermal momentum can be observed through the Rate of Rise (ROR) of bean temperature.

⸻

MAI Duration as a Tool for Balancing Heat Momentum

In reality, the duration of the Maillard Phase reflects how the roaster manages heat. It determines how the beans approach First Crack with an appropriate ROR—supporting good reaction and good development.

• Long MAI Phase → lower heat input → weaker heat momentum

• Short MAI Phase → higher heat input → stronger heat momentum

This explains why extending the MAI Phase can improve results up to a point, but leads to poorer outcomes once it exceeds the optimal range.

At this point, we should redefine the Maillard Phase:

It is the phase that prepares and delivers heat momentum into Development Time.

⸻

Practical Guidelines

So, what ROR at First Crack tends to produce good reactions?

Based on my experience and experiments, a suitable ROR at First Crack generally falls between 7–13°C per minute.

A safe-zone MAI duration is around 3 minutes, give or take slightly.

When roasts consistently hit this window, roasting becomes easier and results are more reliable.

Thank you very much for reading to the end.

⸻

Simplicity in Coffee Roasting – English Edition (Thailand Print)

The English edition of Simplicity in Coffee Roasting, printed in Thailand, has now been completed and is officially available. I’m truly happy to see readers following from many countries. If you’re interested in ordering a copy, please contact the admin of the Preda Coffee Roasting House page.

Early Bird Promotion: 15% off—from 2,500 THB to 2,125 THB, valid until the end of January 2026.

Related Content

The other day, I was talking with a younger friend about the physical mechanisms behind the First Crack—where it comes from and how it happens. Since she used to work in the aviation field, I brought up an analogy about airflow hitting coffee beans, causing changes in air pressure and velocity—much like how airflow interacts with an airplane wing. After explaining, I realized it might be useful to write it down in a way that paints a clearer picture.

การหืนของไขมันและผลึกน้ำตาลในระหว่างตาก : เหตุผลของกลิ่นผักตุ๋นและ Moisture Reversed ในกาแฟตากร้อน

Why Is the Inside of the Bean Darker While the Outside Is Lighter, Causing an Unbalanced Flavor?

A reader asked:

Reader:

“I would like to ask about coffee roasting. I bought your book and tried following it, but I have some questions.